ELIZABETH TAYLOR: “MY KIND OF ACTING”

For the nearly six decades of Elizabeth Taylor’s career, critics and scholars preferred to write about her, rather than her acting. Much ink was spilled on her physical beauty, her striking violet eyes, her fluctuations in weight, her eight marriages, her extravagant jewelry, her conversion to Judaism, and her staunch activism on behalf of HIV research. Not until the 1960s was she awarded two Oscars, the second for Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966), an unattractive role that challenged her reputation for beauty. As late as 2011, she was assumed to have had a “fantastic disregard for the discipline of acting.”[1] A respectful and insightful study of her craft finally appeared in 2012, one year after her death, when Susan Smith carefully interrogated “some of the influences that helped shape Taylor’s professional development.”[2]

My profile focuses on Taylor’s skillful acting through her performance in Rhapsody (MGM, 1954) as Louise Durant—a rich woman, infatuated with Paul Bronte, a classical violinist who throws her over for his music. On the rebound, Louise marries James Guest, a young pianist with whom she falls in love when, in a strategic move to return to Paul, she helps James’ channel his talent into disciplined technique. Rhapsody is both a “woman’s picture de luxe” and a “highbrow” MGM musical,[3] featuring beautifully performed concerti by Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov.

Reviews of Taylor in Rhapsody typified the emphasis on her person. Most paid tribute to her looks, adding perfunctory nods to her craft. “Her wind-blown black hair frames her features like an ebony aureole, and her large eyes and red lips glisten warmly in the close-ups.”[4] She “looks[s] very beautiful, […] wear[s] some gorgeous wardrobe items, which the females will find exciting, [and] handles the dramatics neatly.”[5] Some critics used her life to provide justification for her beauty and, more cuttingly, her talent. On the one hand, “motherhood [in real life] had brought Elizabeth’s beauty to full bloom” on the screen.[6] On the other hand, Rhapsody proves that Taylor can be “a true actress, as she has often been a genuine star, […] because Miss Taylor’s shallow emotional make-up and limited intellectual capacity […] matched perfectly with Louise Durant, a not very bright, but ravishingly sexy heiress.”[7] Around the time of Rhapsody’s release, Richard Brook, who directed Taylor during the 1950s, already recognized “her disappointment that she was not regarded as an actress, but merely as a beautiful girl.”[8] By 1964, she had accepted “the Elizabeth Taylor who’s famous, the one on celluloid” as having “no depth or meaning to me. It’s a totally superficial working thing, a commodity.”[9]

Many reasons lie behind the long-time devaluation of Taylor’s acting, among them the cultural context which positioned beauty and intelligence as mutually exclusive, the patriarchal attitudes of the Hollywood studio system in which Taylor literally grew up, and the practice of acting which, as I have argued elsewhere, is tacit knowledge, like riding a bicycle, which resists verbal description and objective analysis.[10]

Another salient reason, however, lies buried within Taylor’s own seeming underestimation of her acting. She repeatedly denied ever having had “acting lessons.”[11] As late as 2007, she insisted that, “Everything I’ve done I invented.”[12] She also frequently disclaims her expertise, speaking of “my kind of acting, if you can call it acting” and of herself conditionally—“if I’m an actress at all, if I have any technique at all.”[13] Of course, such self-denigration functions as a self-defensive shield that wrests power from the hands of those who sought to denigrate her. More importantly, however, Taylor’s diffidence about her craft peaks at that vulnerable moment, a few years before the release of Rhapsody, when she was transitioning from child star into adult actor. Moreover, this mid-twentieth century moment significantly coincided with the rise of the Method, as promulgated by Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio in New York.

While the Hollywood studios had taken great pains to hide the fact that actors need training,[14] Method actors were provoking loud, public discourse about their schooling. As Strasberg said in 1956, “Actors have been thought about in the past… […] But this is the first time in the history of theatre … that general people—the barbershop and beauty parlor attendants—are discussing [actors’] work.”[15] Taylor reflects this personal and cultural moment when she recalls working on A Place in the Sun (1951) in her “first kind of adult role” with her co-star, Montgomery Clift. While she sees herself as a “cheap movie star,” Clift was “a Method Studio actor,” hence “gen-u-ine.” She “didn’t know what Method meant, but it sounded serious.”[16] In short, given the Method’s growing public prestige, Taylor’s on-the-job training may well have seemed child’s play to her.

Nonetheless, Taylor’s training had been serious. As a child she had entered MGM’s “training ground,” a descriptor used by Lillian Burns, who served there as drama coach from 1936 to 1956.[17] Burns reportedly “gave Elizabeth Taylor her first acting lesson;”[18] and Smith publishes a photograph of Burns coaching the teen-age Taylor in 1947.[19] Burns was one of the influential teachers, who were hired by the Hollywood studios to train their contract players and who taught a pure, pre-Method form of the Stanislavsky System for actor training.[20]

What Burns says of her pedagogy makes sense of Taylor’s denial of having studied acting. “I never ran a school,” Burns recalls. “It was a one-to-one process, a development.”[21] The MGM players, however “raw,” had been hired as professionals, not “students”; and Burns took pains to treat them as such. “I would take the young people right through a script. It wasn’t just training them. I never had a class. They really worked as you would in rehearsal.”[22] In contrast, members of the Actors Studio regularly testified to the importance of their attending Strasberg’s weekly classes.

While Taylor rarely describes her acting, her words always support the Stanislavsky-based training offered at the Hollywood studios. Her anecdote about Mickey Rooney’s advice to her while filming National Velvet (1944) is a case in point. She dramatizes the collision that was then taking place between the Strasberg Method, which demands that actors create personal substitutions from their own lives in service of their acting, and the Stanislavsky System, which expects actors to step imaginatively into the play’s given circumstances and to think the characters’ thoughts—their inner monologues.

In this anecdote, Taylor first identifies Velvet’s given circumstances: she had to cry because “the horse had colic, and of course he was Velvet’s life.” Rooney then suggests to her a personal substitution based on her actual family: “you should think that your father is dying and your mother has to wash clothes for a living, and your little brother is out selling newspapers.” When the cameras finally roll, Taylor uses an inner monologue instead: “all I thought about was the horse being very sick and that I was the little girl who owned him. And the tears came.”[23]

Smith rightly sees Taylor’s tears as those of “compassion” for Velvet;[24] Stanislavsky would have used the Russian word for “empathy.”[25] Smith’s analysis of this anecdote points to the fact that Taylor’s work embodies the central premise behind Stanislavsky’s teaching: that emotional truth in performance results from the actor’s ability to concentrate deeply and actively on the character’s circumstances and thoughts.[26] Strasberg, however, took issue with this very premise; and thus, a stronger appreciation of Taylor’s acting entails a deeper examination of how Stanislavsky and Strasberg differ.

Stanislavsky prompts the actor’s empathy by asking a simple question: “what would you do if the play’s fictional circumstances were real?” As he explains, “the word ‘if’ serves as the lever to take the actor out of real reality and into the world that our art creates.”[27] Every technique in his System, just like the magic if, functions as a “lure” to entice “out of hiding” the emotional “empathy” necessary for a successful performance.[28] Moreover, in Stanislavsky’s eyes, inner monologue provides sure assistance, because a character’s “logical sequence of thoughts is the most stable form of subtext.”[29]

Strasberg forthrightly rejects Stanislavsky’s central premise and his technique of inner monologue. In the first case, Strasberg writes that among his “chief discoveries” was the “reformulation of Stanislavsky’s ‘creative if’” from fictional into actual terms: “the circumstances of the scene indicate that the character must behave in a particular way; what would motivate you, the actor, to behave in that particular way?”[30] In the second case, this reformulation leads the actor to “seek a substitute reality different from that set forth by the play that will help him to behave truthfully according to the demands of the role.”[31] Thus, Strasberg replaces inner monologue (or “thinking exactly what the character is thinking”) with personal substitution (or “think[ing] something real and concrete”).[32]

Taylor recalls bursting into laughter at Rooney’s suggestion of a personal substitution.[33] Her reaction would surely have delighted Stanislavsky, who feared for actors’ “mental hygiene,” when they used personal emotion in their work.[34] More importantly, she would have won the approval of the Hollywood drama coaches, whose interviews and textbooks embrace Stanislavsky’s central premise and techniques. As Lillian Albertson at Paramount asks, “Can you think as [another person] would think; react as [another] would in a given situation?” If not, “you will never become an actor.”[35] Imaginative empathy allows an actor to cry real tears in fictional circumstances. After demonstrating how imagination could bring her to cry over an “ugly bronze lamp on my desk,” Albertson particularly stresses the importance of fiction: “it is not reality that must be striven for. It is seeming reality that must be your goal. […] My tears are just as wet as they would be, if my heart were breaking.”[36]

Consequently, close script analysis lay at the heart of the studio system training. Studying the text illuminates the character’s given circumstances and uncovers the character’s “silent lines,” to use the term advanced by Sophie Rosenstein at Warner Bros for inner monologue.[37] Burns emphasized that “a dramatic coach […] can only help actors to properly interpret and understand a character.”[38] Ultimately, active concentration on a character’s thoughts unlocks emotion during performance.[39] Furthermore, the character’s thoughts are especially crucial when playing to the camera, which Burns called a “truth machine,” because it picks up the smallest physical manifestation of thought. As Burns explains, “You cannot say ‘dog’ and think ‘cat,’ because ‘meow’ will come out [on the screen] if you do.”[40] Her words completely contradict Strasberg’s reasoning.

As in the anecdote above, Taylor betrays her Stanislavsky-based training whenever she speaks seriously about her craft. “Trying to be inside the skin of the person, totally disregarding one’s self, trying to become them, takes tremendous concentration,” Taylor explains. “And if I am portraying something emotional in a scene, I sweat real sweat and I shake real shakes.”[41] Echoing Burns, Taylor writes, “the camera can move in and grab hold of your mind.”[42] Thus, for her, Method actors’ penchant for “transplant[ing] themselves into a personal experience […] is a bit like cheating. I think if you are playing a part, you should not react the way you would personally react; you should react the way the character would react.”[43]

Rhapsody presents an excellent opportunity to examine the physical manifestations of inner monologue on Taylor’s acting, because director Charles Vidor features many moments in which Louise silently reacts to action that takes place around her. For example, near the film’s beginning, Louise is left alone at a restaurant table by Paul, while he entertains the crowd with his violin. Taylor manifests Louise’s disappointment at having been abandoned with a smile that slowly fades and eyes that dart from side to side, as if to check whether anyone notices her sitting alone. Taylor’s physical gestures embody Louise’s inner monologue.

While Taylor’s specific thoughts remain unknowable, they prompt visible, physical changes that express Louise’s emotional reaction to her given circumstances. Despite Burns’ metaphorical comparison of a camera to a “truth machine,” Josephine Dillon, Columbia’s drama coach, more literally explains that “the lenses of the cameras, or the lenses of the human eyes, see only the body, not the thought, nor the wish, nor the emotion, nor the soul—just the body. So it behooves the actor to give the camera or the observer something to look at which has the meaning intended by the story.”[44]

The two most extended sequences of inner monologue in Rhapsody occur when Louise attends first Paul’s, and then James’ concerts. Because the film is structured through a musical pattern of repetition and variation whereby Louise’s scenes with Paul are later replayed in different emotional keys with James, Rhapsody invites the viewer to examine how Louise reacts differently with the two men. At these concerts, Taylor’s work differentiates between the infatuation with Paul that Louise mistakes for love and her actual, unselfish love of James.

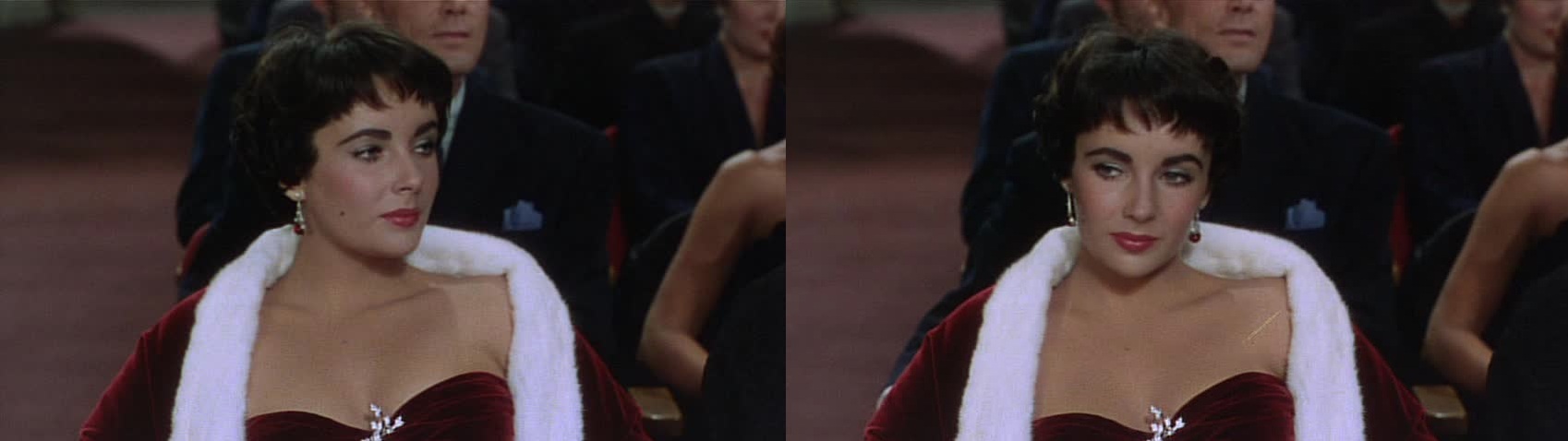

The first sequence is eight minutes long. Nine medium shots of Taylor, sitting in the midst of a crowded auditorium, trace Louise’s changing emotions during the course of Paul’s premiere concert. The given circumstances are these: Paul has refused to see Louise during his weeks of rehearsal, because their relationship distracted him from his music. Louise expects to renew their love affair immediately after his performance. As Paul enters the stage, Taylor applauds energetically, a broad smile on her face. She then settles back into her seat, no smile on her lips, her shoulders covered by her wrap, as if making herself comfortable for a long concert.

Elizabeth Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

As the music plays, she heaves a sigh and, as in the restaurant, glances to either side of the auditorium.

Elizabeth Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

As the music continues, Taylor’s physical movements increase in frequency. Her hands together, she moves her fingers, then drops them back into her lap. A hand moves again into the frame, and she touches a cheek with her gloved fingers.

Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

About midway through the concert, Taylor smiles seductively and uncovers one shoulder, as if anticipating the coming meeting with her lover.

Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

These gestures express Louise’s restless desire for the music to end. Yet, when it does, the woman sitting next to her springs to her feet in applause before Louise moves. Taylor looks at her standing neighbour, who has prompted her to smile and applaud.

Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

Only after this look does Taylor then rise to join the standing ovation. This delayed response suggests that Louise was lost, not in the music, but in her own thoughts at concert’s end. Overall, Taylor’s gestures in this sequence create an inner emotional story of a woman, more in love with being seen as in love, than someone who cares deeply about her lover and what matters to him.

The second sequence is ten minutes long, with seventeen shots, fifteen of which show Taylor in close-up. Just prior to the concert, Louise has told James that she plans to leave him for Paul, but Taylor’s physical work belies Louise’s words. Instead of taking her seat in the middle of the auditorium, Louise arrives just as the music begins and takes an empty seat on the aisle in the last row. Her lateness suggests that she is unsure about attending. In a medium shot, Taylor leans back into the chair to listen, expressing Louise’s unsureness through a pose that looks more uncomfortable than the one at the start of Paul’s concert.

Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

In the fifteen close-ups that follow, Taylor’s gestures continue to express a different emotional journey than that experienced by Louise at Paul’s premiere. While James performs, Taylor begins with constant, but nearly imperceptible motion. Her shoulders strain forward within the frame toward the stage. Her head drifts horizontally from side to side, as if her neck can barely hold it steady. Her lips close then open. These small movements play against a series of changing expressions, each suggesting a different kind of thought. With frowning eyes and lips closed, she expresses concern, perhaps even guilt, over James.

Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

Her eyes drift slightly downward and her lips part, as if in awe at the beauty of the music and her husband’s playing.

Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

As she begins to smile, perhaps proud of James’ talent, she seems to lose herself in his music.

Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

While Taylor had increased her motion over the course of the first concert to suggest Louise’s growing restlessness, Taylor now decreases her motion, suggesting Louise’s deepening absorption in the performance. By the time that Paul arrives, nothing, not even he, can distract Louise from the stage. Taylor’s smile broadens as the music climaxes, and when it ends, her head drops heavily and sharply forward, as if her neck can no longer hold her head upright.

Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

Thus, emotional relief is mirrored in physical release. In the next shot, Taylor first raises her smiling face.

Taylor in Rhapsody (1954)

She then springs to her feet in spontaneous applause. These two swift reactions to the end of the music create physical counterpoints to Louise’s delayed response earlier. In short, Taylor creates a physicalized image of Louise’s active concentration on James’s performance, hence a portrait of self-less love.

“Acting a role does not mean learning lines, cues stage business and set responses,” writes Rosenstein. “It means creating the inner life of the character delineated by the playwright. […] Only when the actor brings into being this inner life—this stream of consciousness of another being—can he be said to be acting creatively.”[45] In Rhapsody we see, over and over again, Taylor doing precisely this kind of inner monologue work. The result is a beautifully detailed, emotionally moving performance.

Sharon Marie Carnicke (Professor and Associate Dean of Dramatic Arts at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles) is best known for her groundbreaking research on the relationship between the Stanislavsky System and the American Method in Stanislavsky in Focus (2nd ed). She has also published widely on film acting and co-authored Reframing Screen Performance with Cynthia Baron. Her award winning translations of Chekhov’s plays, Chekhov: 4 Plays and 3 Jokes inform the basis for her most recent book, Checking out Chekhov.

[1] Hilton Als, “The Improbable Elizabeth Taylor,” The New Yorker, March 24, 2011,

<http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2011/03/elizabeth-taylor-hilton-als.html> Accessed March 27, 2014.

[2] Susan Smith, Elizabeth Taylor (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 88.

[3] Newsweek, March 8, 1954 and Wanda Hale, “Highbrow Musical at Music Hall,” Daily News, March 12, 1954 (Clippings, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Pictures, Los Angeles).

[4] Bosley Crowther, “The Screen: Drama with Music Bows,” New York Times, March 12, 1954,

<http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9A03E6D71039E632A25751C1A9659C94

6592D6CF> Accessed March 27, 2014.

[5] Frank Quinn, Mirror, March 12, 1954 (Clipping, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Pictures, Los Angeles).

[6] Alexander Walker, Elizabeth: The Life of Elizabeth Taylor (New York: Grove Weidenfeld,

1990), 153.

[7] Lawrence J. Quirk, The Great Romantic Films (New Jersey: Citadel Press, 1974), 167.

[8] Quoted in Susan D’Arcy, Elizabeth Taylor: A Biography (Surrey: LSP Books, 1982), 15.

[9] Elizabeth Taylor, Elizabeth Taylor: An Informal Memoir (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 169.

[10] Sharon Marie Carnicke, Stanislavsky in Focus: An Acting Master for the Twenty-First Century, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2009), 72.

[11] Taylor, 40.

[12] Ingrid Sischy, “Elizabeth Taylor: Hello,” Interview Magazine, February 2007, 169-91 (Clipping, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Pictures, Los Angeles), 191.

[13] Taylor, 49; 162.

[14] Cynthia Baron and Sharon Marie Carnicke, Reframing Screen Performance (Ann Arbor:

University of Michigan Press, 2008), 18-23.

[15] Quoted in Carnicke, 10.

[16] Taylor, 48.

[17] Lillian Burns (Sydney), transcript of interview on August 17, 1986 (Performing Arts Oral History Collection, Southern Methodist University), 2.

[18] Los Angeles Examiner, November 29, 1956 (Clipping, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Pictures, Los Angeles).

[19] Smith, 94.

[20] Baron and Carnicke, 27.

[21] Burns, 2.

[22] Ibid., 13; 7.

[23] Taylor, 162-3.

[24] Smith, 118-20.

[25] Carnicke, 214.

[26] K. S. Stanislavskii, Sobranie Sochinenii, 9 vols., vol. 2 (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1989), 144-83. Translations are mine.

[27] Ibid., 98-9.

[28] Ibid., 313.

[29] K. S. Stanislavskii, Sobranie Sochinenii, 9 vols., vol. 3 (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1990), 475. Translations are mine.

[30] Lee Strasberg, A Dream of Passion: The Development of the Method (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1987), 85-6.

[31] Ibid., 85-6.

[32] Ibid., 86.

[33] Taylor, 163.

[34] Carnicke, 153.

[35] Lillian Albertson, Motion Picture Acting (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Co., 1947), 47-8. Italics are hers.

[36] Albertson, 60. Italics are hers.

[37] Sophie Rosenstein, Modern Acting: A Manual (New York: Samuel French, 1936), 60-1.

[38] Thomas M. Pryor, “Pep Talk from a Dramatic Coach,” New York Times, February 24, 1954 (Clipping, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Pictures, Los Angeles).

[39] See Albertson, “Concentration,” 55-6 and Rosenstein, “Concentration,” 48-66.

[40] Burns, 2.

[41] Taylor, 162.

[42] Ibid., 166.

[43] Ibid., 164.

[44] Josephine Dillon, Modern Acting: A Guide for Stage, Screen, and Radio (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1940), 18.

[45] Rosenstein, 3.